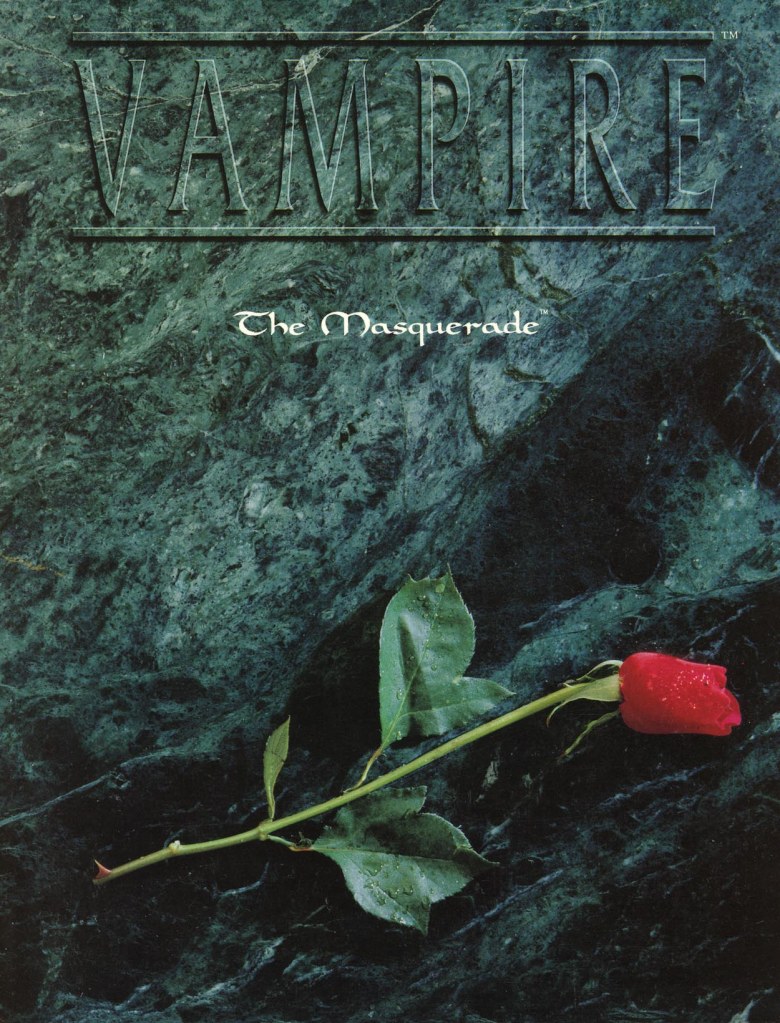

I previously and somewhat cryptically alluded to the fact that I have Vampire: The Masquerade to thank for my current career. While that is true, my road from picking up that marble & rose cover book in 1991 and cashing my first paycheck as a game designer isn’t a direct one. There were lots of turns, temporary rest stops, and more the a few dead ends. Nevertheless, I could have quite easily found myself in another line of work had it not been for Vampire.

I was a TSR fanboy, having come into the role-playing hobby via D&D like so many others. At the time, roughly between 1980 and 1990, TSR games were the easiest to find in local hobby shops and toy stores. I played D&D, Top Secret, Gamma World, Star Frontiers, Marvel Super Heroes, and even the much maligned The Adventures of Indiana Jones. West End Games’ Star Wars and FASA’s Shadowrun both dropped as I entered my final years of high school and were a nice diversion from D&D, but we always drifted back to rolling d20s and killing monsters.

I graduated high school in 1990 and played in an AD&D campaign during my freshman year. It was fun, but not as fun as it had been in the past. Part of it was being an “adult” and on my own for the first time. There wasn’t a lack of opportunity for entertainment on a weekend or even a weekday night in college (and many of those opportunities also included beer and women), so the dew was off the RPG rose then. And doing anything for a decade is bound to get a little tiresome. I found myself seriously considering dropping RPGs as a hobby and doing something else for fun.

My time at the State University of New York came to an abrupt and unexpected ending in June of 1991. As it turns out, despite the fact I was paying the SUNY system, they still expected you to show up to class once in a while. MY GPA was in the toilet and the university suggested that I try something else—anything else—some place other than there. Much to parents’ dismay, I had been kicked out of college, but it was suggested that if I got my grades up, I could apply for readmission. In September of 1991, I enrolled in the local community college with hopes of returning to the SUNY system for the Spring ’92 semester.

I didn’t do any gaming while at community college, but I did pick up the occasional RPG book or issue of Dragon magazine. Old habits die hard, after all. One of those issues was the November ’91 issue (the same month as my 19th birthday), Dragon #175. That issue featured a Role-playing Reviews covering three horror RPG products: Dark Conspiracy, “Blood Brothers” (for Call of Cthulhu), and some game called Vampire: The Masquerade from a company I’d never heard of before.

I liked a good horror film or book, but I wasn’t particularly enamored of vampires. I had read Interview with a Vampire by then and had seen The Lost Boys and Fright Night, but was far from a fang fan. I was more of a ghost story guy. But, in the review, author Allen Varney summed up his piece with “If you’re up for a potent and even passionate role-playing experience, look for this game.” That stuck with me. Maybe my problem with RPGs was that my tastes had matured and I needed something more than killing orcs and taking their stuff? I promised myself I’d track down Vampire: The Masquerade and see how it delivered a potent and passionate experience.

The problem was I couldn’t find a copy. My friendly local game shop, Man at Arm Hobbies, did have a copy of Nightlife (co-written by Bradley McDevitt whom I now work with at Goodman Games). I liked Nightlife, especially since it was by default set in New York City (right in my backyard) and you could play a ghost (see previous paragraph), but it wasn’t quite what I’d hoped or was looking for.

Somehow, I eventually tracked down a copy of Vampire. It might have been on another trip to Man at Arms or maybe different store. And while I can’t remember where I bought it, I do remember where I read it for the first time. I was sitting in the dining room at my friend Carl’s house, flipping through the book. The opening in-world fiction written to Mina Murray from Dracula opened the floodgates of my imagination. This was something different. But the real moment that changed my life came on p. 36 in the section entitled “Automatic Success.”

In short, Vampire included the mechanic where if the number of dice in your dice pool equals or exceeds the difficulty of the task you need to perform, you automatically succeed. In other words, if the Difficulty is 5 and I have 6 dice in my dice pool, there’s no need to roll. Other RPGs had suggested you don’t need to roll to accomplish easy tasks anyone can do, but this was the first time I’d seen a mechanism that allowed you to succeed on things that might be challenging for the average person.

It’s been 34 years since I read that section and I still remember how much it blew my mind. That was the moment I stopped thinking of myself as a lapsed DM and as a potential Storyteller.

The rulebook only got better as I read it further. As a confirmed punk with music tastes that included Dead Kennedys, The Misfits, Black Flag, The Damned, The Exploited, etc., I found lyrics to songs I knew and loved leading off sections of the book. Hell, the entire milleu of the game was “Gothic-Punk.” It was almost as if these White Wolf folks were cool like me!

When January of ’92 rolled around, I’d gotten my GPA up and was welcomed back to SUNY New Paltz. I left all my D&D books at home when I packed for my trip back to the dorms. However, tucked into my back was my copy of Vampire: The Masquerade and a bag of d10s. I had big plans that semester, ones which ultimately led to a Vampire chronicle that lasted for years in different incarnations with different players, a chronicle that began on regular Sunday nights by candlelight in the now-former DuBois Residence Hall.

Vampire kept me in the hobby for another decade and made me rethink what you could do with a tabletop RPG. And while I did drift out of the hobby again for a time in the mid-2000s, the lessons I’d learned from V:tM stayed with me. I never again considered dropping the hobby for good and when I came back in 2008, I found myself on the path to becoming a freelance game designer and writer. Had it not been for discovering Vampire when I did, I know the odds of me returning to the hobby would have been slim and I might not currently have the job I do in the industry. Let’s just say I owe a boon to Vampire, in all its shapes and forms, and it’s a debt I’m happy to oblige.