I want to tell you a story

‘Bout a little man, If I can

A gnome named Grimble Grumble

And little gnomes stay in their homes

Eating, sleeping

Drinking their wine

–“The Gnome” by Pink Floyd

When one thinks of gnomes, one is prone to think of them in the context of the Old World, not the New. Whether as earth elementals in the occult philosophy of Paracelsus, a dwarflike creature dwelling underground, or the pointy red-hat waring variety from the book by Wil Huygen, gnomes—outside of Dungeons & Dragons—are creatures of European origin and would seem out of place here in the Americas. Or at least that’s what one would think if they never ventured into the ancient mountains known as the Catskills.

As it turns out, the Catskill Mountains have a long history of being the partying place for a race of short humanlike creatures that are quite evidently not human. Stories of these beings go back to before European contact in the folklore of at least three different indigenous cultures. Henry Hudson, the first European to sail up the river named after him and pass under the shadows of the Catskills, was said to have had his own encounter with these beings. Do they still dwell in the mountains now better known for the Borscht Belt than mythical creatures? Let’s take a look and see what we can do with this bit of folklore.

There are two major folktales involving the Catskill gnomes concern one purportedly told by the Mohegan people who made their home in the region and the second involving Henry Hudson.

The first folktale is recorded in Myths and Legends of Our Own Land by Charles M. Skinner, published in 1896. According to Skinner, the Mohegan people spoke of a natural amphitheatre located behind the Grand Hotel, which once stood in Highmount, NY. This place was said to be the gathering site of small beings who “worked in metals, and had bushy beards and eyes like pigs.” These beings would assemble on the ledge above the amphitheatre and dance the night away under a full moon. They were said to brew a potent liquor, one that shortened the bodies and swelled the heads of anyone who drank it. Skinner reports that Hudson and his crew encountered these gnomes when visiting the mountains. The short beings held a party in his honor and invited Hudson and the crew to drink their mountain moonshine. As a result, the crew went away shrunken and distorted, and it was in this guise that Rip Van Winkle would encounter them a century later.

The second folktale comes from a story recorded by S.E. Schlosser in Spooky New York. Schlosser writes that Hudson and crew heard the sound of music echoing from the hills as the Half Moon lay at anchor in the shadow of the Catskills. Hudson and crew went ashore to seek out the source of the music, only to find “a group of pygmies with long, bushy beards and eyes like pigs” dancing and capering around a fire. Hudson recognized the beings as the metal-working gnomes some of the native tribes had spoken of.

The gnomes quickly spotted the party crashers and welcomed them with a cheer. Long into the night, the crew drank with the gnomes and played nine-pins. Hudson sipped only a single glass of the homebrewed hooch and “spoke with the chief of the gnomes about many deep and mysterious things.”

Realizing how late it had become, Hudson looked around to gather his men, only to discover he couldn’t see them. All he glimpsed was a large group of gnomes laughing around the fire. To his amazement and horror, Hudson recognized several of the gnomes as his crewmen, now transformed into short creatures with heads “swollen to twice their normal size, their eyes were small and pig-like, and their bodies had shortened until they were only a little taller than the gnomes themselves.”

Alarmed, Hudson pressed the chieftain for an explanation and he was assured that the change in his crewmen was the result of drinking the gnomes’ brew and that the transformation would wear off when the sailors sobered up. Hudson, fearing what else might be in store for his men, quickly gathered up his miniaturized mariners and hustled them—drunkenly—back to the Half Moon. When the crew awoke in the morning, it was with terrible hangovers, but thankfully back to their normal shapes and forms. In one version of this tale, one of the crewmen was overlooked in the rush to get everyone back to the ship and remained in the gnomes’ company, permanently transformed, ever after.

The tale has a further addendum. In reality, Hudson’s crew mutinied on a subsequent voyage to locate the Northwest Passage. In 1610, after being trapped in the ice for the winter, the crew set Hudson and eight other sailors adrift in Hudson Bay and they were never seen again. Legend says that every 20 years, a fire appears in the amphitheater and the sound of music echoes through the mountains. The gnomes would hold a party every two decades and the ghosts of Hudson and his men would join the festivities at midnight. Until dawn, the ghosts and gnomes would play nine-pins, the sound of the ball rolling like thunder and bolts of lightning streaking across the sky when the pins fell. For those of you keeping track, the next gathering is scheduled for September 3rd, 2029, somewhere near the former site of the Grand Hotel on Monka Hill.

Meet the Locals: The Catskill Mountains are overlapped by three indigenous language groups. You have (roughly) Delaware speakers to the south and southwest, Algonquin speakers to the southeast, east, and northeast, and Iroquois speakers to the west and northwest. Each one of these cultures has their own mythology that includes short humanlike beings.

Among Algonquin-speaking peoples, you find Pagdadjinini, the little people of the forest. Their name means “wild man” and they’re known to be mischievous, but generally good-natured. In Delaware-speaking cultures, you have Wemategunis, a little people about as tall as a man’s waist. Like the Pagdadjinin, the Wemategunisare are mischievous, but generally benign forest spirits, although they can become dangerous if disrespected. They have the ability to turn invisible and have immense strength. They may help people who are kind or who tolerate their mischievous pranks with good humor.

Lastly, you have the Jogah from the myths of the Iroquois Confederation. The Jogah are a small humanoid nature spirits, sometimes called “dwarves” by Europeans. Their size varies, with some cultures saying they’re only knee-high, while others stating the Jogah stand 4’ tall. However, the Jogah are often invisible revealing themselves mostly to children, elders, and medicine people. There are several different types of Johah, notably the Gahongas who are renowned for their great strength, capable of moving boulders many times their size. According to legends, Gahongas live on rocky riverbanks and in caves. There are also the Gandayah or Drum Dancers, who are always invisible and only the sound of their drums indicate their presence. The Gandayah are known to help the Iroquois peoples with their crops. Lastly, the Ohdows are a gnomes who live under the earth and are said to keep serpents and other subterranean monsters in check.

Any one of these “little people” could have been the gnomes Hudson and his men met that night, but both the Wemategunis and Jogah seem to make the best fit.

Fun Guys from Yuggoth: Strange creatures in the mountains should sound very familiar to anyone whose read The Whisperer in Darkness, H.P. Lovecraft’s story about the Mi-Go, an alien race from Pluto who dwell in the hills of Vermont where they mine minerals not found on their home world. The Mi-Go possess advanced scientific technology and are served by human (or at least human-seeming) agents to hide their presence from outsiders. The Catskills could very well hide a Mi-Go mining colony extracting the same minerals as their Vermont-dwelling kin. And while the Mi-Go themselves don’t resemble the creatures Hudson and crew encountered in the slightest, they demonstrate the ability to perform miraculous surgical procedures on humans. It wouldn’t take much effort for the Mi-Go to greatly modify native humans, altering them to resemble figures from legend. What better way to keep the unwanted away then by “haunting” the mountains with the forest and mountain spirits the indigenous people already believe to be there? Perhaps the physical alterations to Hudson’s crew wasn’t the result of gnome liquor but alien rays targeted at the sailors by hidden Mi-Go? The missing crewman one version of the tale mentions might have been captured by Fungi of Yuggoth and brought (or at least his head was) to Pluto for further examination and interrogation.

As Above, So Below: One last option could be that the gnomes were just as much strangers to the mountains as Hudson and his men. Their small stature would greatly benefit any race dwelling underground, making any number of legendary subterranean civilizations as the possible origin of the gnomes. Derro (the Shaver Mystery ones, not the D&D kind), former Hyperborean slaves a la Mike Mignola’s Hellboy depictions, faeries, troglodytic humans driven underground, or even lost Tibetan tunnel diggers who’ve gone native could all be the real gnomes in question.

Strange Vapors: The account mentions that the crew played nine-pins with the gnomes, which seems odd even in an already strange account. It appears the game was in progress when Hudson and his crew arrived on the scene, leading one to wonder where the gnomes got the all the elements to play the nine-pins, let alone hear about this European game. Maybe that’s because the gnomes were all in the minds of the European explorers? The fires spotted by the Half Moon may have been some sort of natural phenomenon akin to the “swamp gas” used to dismiss UFO sightings by Project Bluebook. A subterranean gas, one with hallucinogenic effects and flammable or phosphorescent properties, may have leaked from deep underground and affected the men when they investigated. The missing crew man could have wandered off, perhaps falling to his death off a cliff or down the crevasse that the gas emerged from, his body never found.

Henry Hudson, Wherefore Art Thou? I can’t end a post involving Henry Hudson in a starring role without briefly touching upon the circumstances of his disappearance from the mortal realm. As noted above, Hudson, along with his son and seven crewmen, where set adrift in a small shallop (a type of open boat) in James Bay in 1611 by mutinous crewmen after having been force to overwinter there while exploring Hudson Bay. The nine men briefly pursued Hudson’s former ship, the Discovery, before the vessel raised sails and left the shallop behind. That was the last known sighting of Hudson and the rest. Searches conducted in 1612 and 1668-1670 failed to find any sign of Hudson or his men. Author Dorothy Harley Eber collected testimonies in the 20th century from Inuit residents of the area that revealed the existence of old stories dating back centuries that might shed light on Hudson’s fate. The stories spoke of the arrival of an old white man with long white beard and a young boy who were taken in by the Inuit people, despite their never having seen a European before. The old man soon died, and the boy was tethered to one of the homes so he wouldn’t run away. The ultimate fate of the boy and the man’s corpse were unknown.

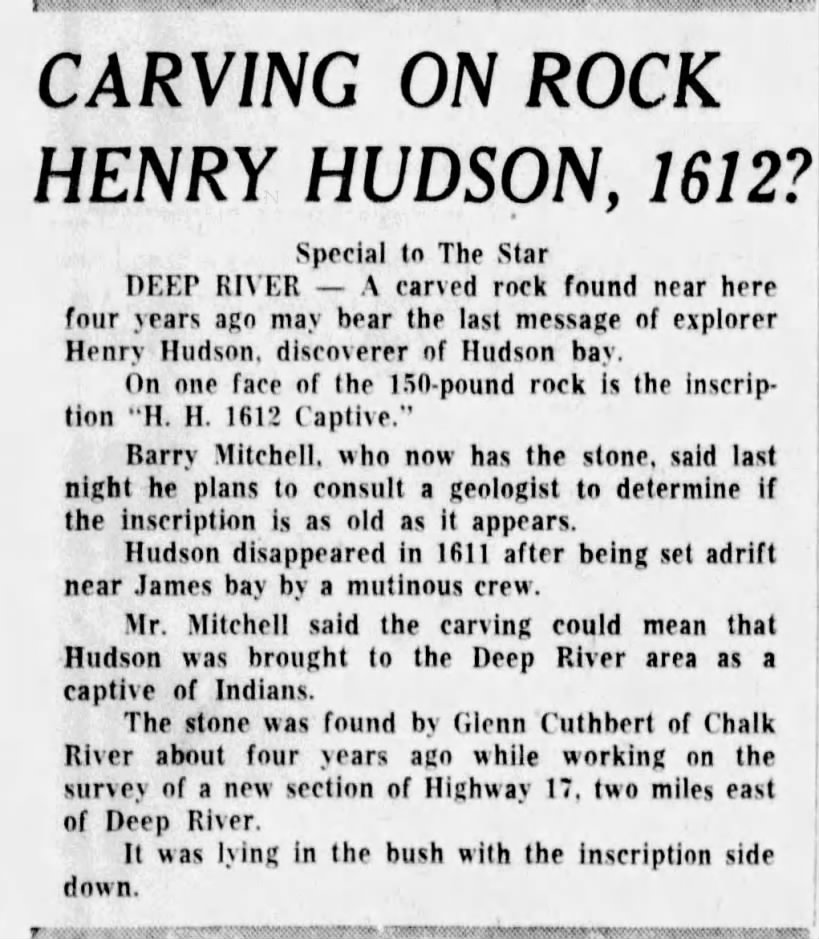

In the late 1950s, a 150 lbs. stone was discovered near Deep Rive, Ontario, more than 350 miles away from James Bay. The stone was carved with the initials “H.H.”, the year 1612, and the word “captive.” While the date of carvings couldn’t be determined, the style of the letters was consistent with 17th century English maps. Hudson, like the crew of the H.M.S. Terror and Erebus two centuries later, was swallowed by the Great White North, leaving only legends behind.

Weird Americana Connections: The Catskills aren’t the only place in the American Northeast that’s said to be home to small creatures associated with oversized heads. Just across the New York/Connecticut border come tales of a much more ferocious type of short humanoids, ones who’ve been said to attack people. Join me next time when we put are noggins to work delving into the legend of the Connecticut Melon Heads.